Matrix transposition is one of the most common things computers do as this operation creeps itself into many day-to-day computer operations

From optimized 1D convolution kernels that make gaussian blurs possible to optimized matrix multiply algorithms that are the heart of many machine learning operations, it is safe to say this operation has received adequate research

The naive way to transpose a matrix

Using the earlier representation of a matrix, matrix transposition is a simple data access and data write for every element in the array

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

pub fn transpose_scalar(in_matrix: &[u8],

out_matrix: &mut [u8],

in_stride: usize,

out_stride: usize)

{

for i in 0..out_stride

{

for j in 0..in_stride

{

out_matrix[(j * out_stride) + i] = in_matrix[(i * width) + j]

}

}

}

This is simple, ergonomic, works, does nothing fancy and gets the job done and it’s slow.

The latter is what comes to pinch us here.

From a CPU standpoint, array accesses to in_matrix happen linearly, i.e we move from start to end, which is great, and the cpu can prefetch elements, but accesses to out_matrix happen very stride-wise, assuming out_stride was 800, accesses to B for 5 iterations would be

1

0 800 1600 2400 3200 4000

This makes it a bit harder for prefetch logic to kick in, and even when it does, it causes a lot of cache wastage as we are loading a whole cache line to write one value.

Tiled matrix transpose

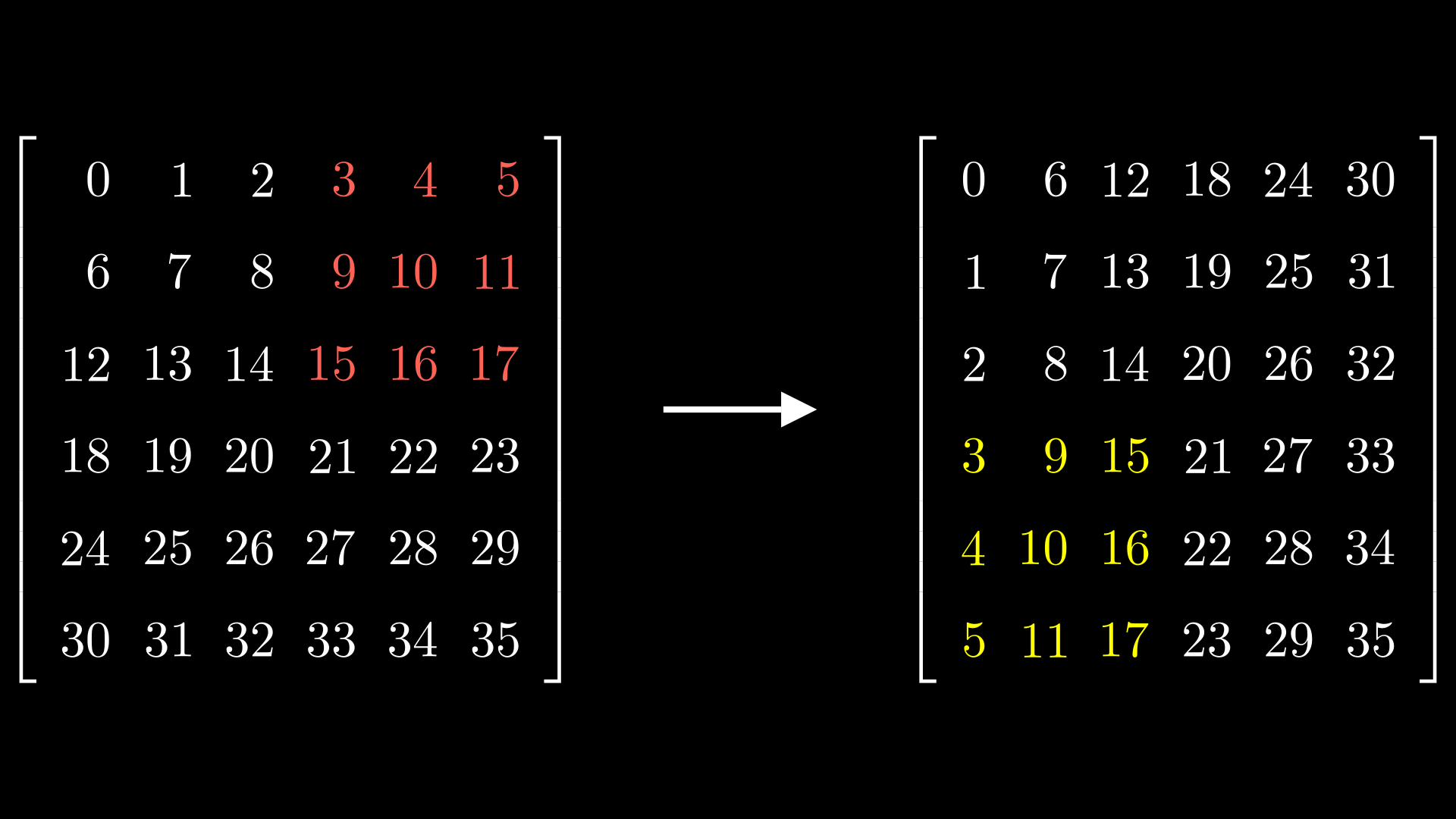

Another way to look at matrix transposition is that a matrix transposition can be viewed as a submatrix transposing followed by figuring out where the newly transposed submatrix should go to.

E.g in the above image, we can transpose the three-by-three matrix (coloured in red) and if we place it at the position coloured yellow, we have achieved transposition.

Or more generically, we are trying to achieve…

But why transpose sub-matrices? Well,the most important is that cache misses reduce significantly for the operation. The sub-matrices have good spatial locality, hence we use the cache better.

But there is another thing with sub-matrices, sub-matrix transposes can be done in SIMD registers.

If we use a small enough sub-matrix, we can get rid of intermediate buffers to store the results of the matrix transposition and use SIMD instructions to perfom matrix transposition inside SIMD registers.

Intel has a famous _MM_TRANSPOSE4_PS that can transpose floats in four SIMD registers so if we choose a 4 by 4 sub-matrix of floats, we can do some tilling to get it to work (with some caveats of course 1)

For my use case, I happened to be working with u8’s/bytes/chars hence I didn’t have the luxury of enjoying macros.

The only difference arising is that I just need to roll up my routine, which does a submatrix transpose of any size that comfortably fits into a SIMD register, and am 8 by 8 transpose seemed to hit the spot.

There is a small awkward issue with this, that being the fact SSE register is 128 bits while 8 u8’s give me a total of 64 bits, meaning that data loading and storing are a bit awkward but otherwise everything is good.

The 8 by 8 SSE transposition algorithm is not my own, credits to Hamid Buzidi(powturbo) for the Stack Overflow answer.

So a high overview of the implementation we are trying to implement is.

- Load a submatrix

- Transpose the submatrix

- Write the submatrix.

So let’s get on with it

Loading data

SSE registers usually fit 16 bytes in them, but for our use case we are working with a 8 by 8 sub-matrix.

To load data into it, we use

_mm_loadl_epi64to only load 8 bytes into the lower half and then we interleave the two subsequent loads into one register using_mm_unpacklo_epi64instruction. This allows us to pack two rows separated by a stride into a singlexmmregister.The effect is that we have two rows of our sub-matrix inside one SSE register,hence we just need 4 registers to hold our 8 by 8 sub-matrix

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

pub unsafe fn transpose_inner(

in_matrix: &[u8], out: &mut [u8],

in_stride: usize, out_stride: usize,

)

{

let pos = 0;

// Load data from memory

// Load 64 bites to ensure we only take 8 u8's

let mn_0 = _mm_loadl_epi64(in_matrix[pos..].as_ptr().cast());

pos += in_stride;

let mn_1 = _mm_loadl_epi64(in_matrix[pos..].as_ptr().cast());

pos += in_stride;

// pack the first row with the second row

let rw_01 = _mm_unpacklo_epi64(mn_0, mn_1);

// repeat this 3 more times

- Transposing

Use pushfb to perform a lookup that does some data moving for us.

1

2

3

4

5

6

let sv = _mm_set_epi8(15, 7, 14, 6, 13, 5, 12, 4, 11, 3, 10, 2, 9, 1, 8, 0);

//

let ov_0 = _mm_shuffle_epi8(rw_01, sv);

let ov_1 = _mm_shuffle_epi8(rw_23, sv);

// Two more times

pushfb is a pretty nifty instruction we can use to do some data moving within a SIMD register. It’s usually hard to grasp but it has a nice magic to it.

To understand what the shuffle will do, think about it like this, if the source register rw_0 was an array from 0-15, the shuffle instruction would move the data to be the same as itself, i.e 15,7,14 ,etc, etc in a single cycle, pretty neat.

We then unpack and interleave the data until we have two adjacent rows next to each other in the registers.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

// repeat this two more times

let iv_0 = _mm_unpacklo_epi16(ov_0, ov_1);

let iv_1 = _mm_unpackhi_epi16(ov_0, ov_1);

// repeat this again two more times

let av_0 = _mm_unpacklo_epi32(iv_0, iv_2);

let av_1 = _mm_unpackhi_epi32(iv_0, iv_2);

//...

- Storing

To store the values, we write high and low values of the register to different destinations, separated by stride. extracting the high value into a lower value is done by a _mm_unpackhi_epi64 instruction and we store with _mm_storel_epi64 to only store the lower 64 bits of the xmm register.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

// Extract the higher part of the register since we will be writing it

// to a different stride, (one store should only add 8 bytes)

let sv_0 = _mm_unpackhi_epi64(av_0, _mm_setzero_si128());

let mut pos = 0;

_mm_storel_epi64(out[pos..].as_mut_ptr().cast(), av_0);

pos += out_stride;

_mm_storel_epi64(out[pos..].as_mut_ptr().cast(), sv_0);

pos += out_stride;

// Repeat this 6 more times.

And that’s it.

To recap,doing SIMD matrix transposition is:

- Load a sub-matrix into a SIMD register.

- Perform in-place matrix transposition.

- Write the data out to the appropriate destination

Benchmarks

To see which one is faster, we can simply do a matrix transposition,utilizing Rust’s benchmark facilities (which require a nightly compiler)

The benchmark routine looks like this,

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

// -- Sniped ---

#[bench]

fn transpose_benchmark(b: &mut test::Bencher)

{

let width = 800;

let height = 800;

let dimensions = width * height;

let in_vec = vec![255; dimensions];

let mut out_vec = vec![0; dimensions];

b.iter(|| {

// transpose scalar or vector

})

}

It transposes an 800 by 800 matrix(medium size) array out of place and we time how many nanoseconds it takes to perform a single iteration.

And the results.

| Test | ns/iter |

|---|---|

| transpose_scalar | 496,739 ns/iter (+/- 38,252) |

| transpose_sse | 68,020 ns/iter (+/- 7,733) |

Results are reproducible on x86 hardware

Yep, that’s a 7x improvement right there.

Further Reads

- Nvidia’s blog on Tiled matrix transposition on the GPU: https://developer.nvidia.com/blog/efficient-matrix-transpose-cuda-cc/

Footer

Only works for matrices whose widths and heights are multiples of 4 ↩